Mali, November 2025: Fog of war and propaganda

Crisis in Mali in November 2025: JNIM blockade of Bamako, widespread clashes, fog of war, and weak signals to watch out for

NorthAfrica Intel

11/6/202510 min read

Mali, November 2025 - Fog of war and social media

NAIntel Briefing note #001

Distinguishing fact from fiction in the current situation in Mali is no easy feat. The fog of war (the term used to describe the uncertainty and confusion inherent in conflicts) is compounded by massive disinformation and propaganda from both sides, amplified by social media. In this case, JNIM and FAMa are waging an information war in which every event is disputed online, making it difficult to distinguish between facts and manipulation. This note aims to take stock of the current situation, define the forces involved, and identify the weak signals to watch for in order to anticipate future events.

Operational situation

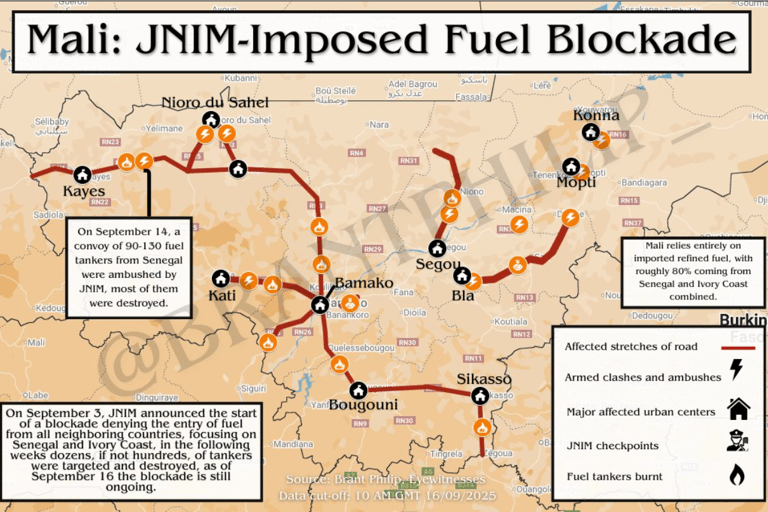

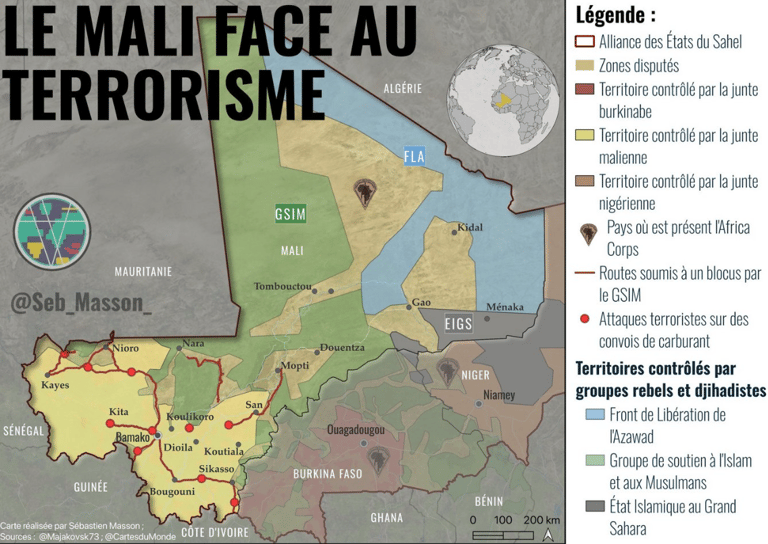

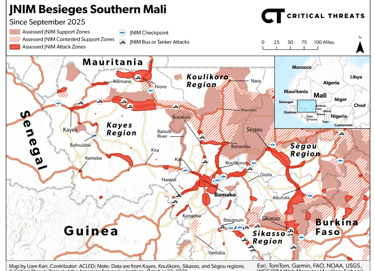

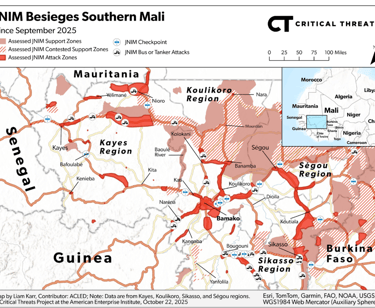

Mali is currently going through a critical phase of destabilization resulting from Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin's (JNIM, an armed group affiliated with Al-Qaeda) blockade of fuel supply routes from Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal, and Mauritania, with the aim of putting pressure on the military leaders, headed by General Assimi Goïta.

This blockade, which began in early September 2025, has intensified since mid-October, paralyzing Bamako and the central and southern regions of Mali. Attacks on tanker convoys have led to severe shortages: endless queues at gas stations, the suspension of schools and universities, and a sluggish economy. Some attacks are documented by the JNIM group itself on social media. At least 50 trucks have been destroyed since mid-September, according to ACLED, isolating government garrisons and exposing civilians to increased vulnerability.

The Malian Armed Forces (FAMa), supported by Africa Corps (formerly Wagner), a Russian paramilitary organization, are conducting sporadic counteroffensives: air strikes by Mi-8 helicopters and Turkish Bayraktar Akinci drones on JNIM positions in Ségou and Sikasso, with the aim of repelling the JNIM (207 deaths according to ACLED).

However, the FAMa are struggling to secure vital routes: fighting is concentrated in a Bamako-Ségou-Kayes arc, less than 100 km from the capital, where the JNIM group is attempting to exploit logistical weaknesses to wage a war of harassment and attrition.

Main actors

FAMa (Malian military) + AfricaCorps (Russian paramilitary group):

Led by General Assimi Goïta since the coups of 2020-2021

Number of combatants: Approximately 35,000 men in total (in 2022)

FAMa: Approximately 34,000 men, but not all of them are mobilized in the center and south of the country. It is difficult to estimate how many soldiers are mobilized to fight JNIM.

AfricaCorps: Approximately 2,000 Russian paramilitaries (specializing in air support and intelligence).

Strategy: Hybrid counterinsurgency, search and destroy JNIM camps with aerial reconnaissance, protect fuel convoys, protect civilians

Objective: Ensure effective control over the entire Malian territory

JNIM - Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin

Group led by Iyad Ag Ghali, formed from the merger of Islamist armed groups that had previously fought French troops during Operation Serval. These groups include al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) (originally based in Algeria) and three Malian Islamist armed groups: Ansar Dine, Al-Murabitun, and Katiba Macina.

Number of combatants: 6,000 to 8,000 men.

JNIM: difficult to estimate, the Washington Post suggests 6,000 men.

Azawad movements (CSP, formerly CMA): ~2,000 Tuareg/Arab rebels in the north (Kidal, Gao) who have formed an opportunistic coalition with JNIM against Bamako. The two groups won a joint victory in Tin Zaouatène in July 2025, a major defeat for Wagner. As secessionists, their motivations are not the same as JNIM's, but they share a common enemy.

Strategy: Asymmetric blockade and harassment warfare. Financing through hostage-taking and capture of fuel convoys for logistical purposes.

Objective: Trigger a collapse of the Malian state, spreading to Burkina Faso and Niger

Timeline of clashes between FAMa and JNIM

March 2017: Creation of JNIM (merger of AQIM, Ansar Dine, and other groups)

First attacks:

-Attack on a MINUSMA base in Timbuktu. 3 UN peacekeepers killed.

-January 2018: JNIM attack on a military camp in Soumpi; 14 FAMa soldiers killed.

-September 2024: First direct attack in the capital city, Bamako;

Large-scale attacks (increased intensity, volume, and resources used):

-June 2025:

Assault on Timbuktu. JNIM targets military base and airport; 60 FAMa soldiers killed;

Ambush in Boulikessi (center of the country). Heavy losses for the FAMa, between 30 and 90 dead according to sources. This ambush marks the first large-scale use of IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices).

-July 2025 :

Offensive on Kayes. Simultaneous attacks on seven locations; the FAMa repel these attacks.

Reports also mention the use of civilian drones hijacked for military purposes by JNIM. Tactical evolution with aerial IEDs.

Blockade of Bamako - clashes spread to large parts of the territory.

-November 2025 : Blockade of fuel convoys. Attacks on convoys, retaliation by the FAMa - the situation is still ongoing.

Fog of War and Propaganda

Difficulty for traditional media outlets to report the facts

Traditional international media outlets are struggling to cover Mali because access to the country is restricted and the situation is chaotic and dangerous. The Malian military in power is imposing strict accreditation requirements and limiting entry visas. Some French media outlets have been banned from Malian territory, amid suspicion given the history between the French authorities and the current Malian government. However, international journalists are not present on the ground either, as conditions are precarious and risks come from both sides: kidnapping by JNIM and disappearance orchestrated by the government. Fragmentary and uncorroborated information leads to unfounded assumptions; for example, the Wall Street Journal prematurely announced the fall of the Bamako government without taking sufficient account of the real balance of power on the ground.

Result: no on-site investigations, forcing reliance on secondary sources and pushing those wishing to learn about the Malian crisis to turn to social media.

Note: There is a clear information vacuum, allowing biased intermediaries to filter information coming from the front lines.

Propaganda on social media... including from interested third parties

Networks such as X and Telegram are the main battleground.

JNIM posts videos of ambushes or spectacular victories, often exaggerated, on Telegram (official Al-Zallaqa channel) in order to boost the arrival of new recruits and create fear among the ranks of the FAMa.

This was the case with JNIM's assault on Soumpi; initial posts on X reported a successful operation by JNIM, only for it to emerge a few hours later that the outcome of the fighting was more nuanced.

Some accounts also repost fake news favorable to JNIM, although it is impossible to determine whether these accounts are formally linked to the armed group. A false note from the Chief of Staff of the Burkinabe Army circulated on X, allegedly revealing a disagreement between Burkina Faso and the Malian authorities. The obvious aim of such posts is to undermine Malian public support by casting doubt on the unity of the ESA countries.

The FAMa are responding on X (@DirpaFa) with triumphant statements about “successful airstrikes,” the results of which are difficult to verify. Furthermore, the inauguration of the Bougouni lithium mine on November 3, intended to reassure the population, contrasts sharply with the proximity of the fighting and projects an illusory image of “normality.”

Pro-AES accounts and Russian bots have also been caught red-handed spreading fake news.

A publication claimed that the Malian army had shot down a JNIM helicopter, when in fact it was a Senegalese army helicopter crash dating back to 2018.

Another post, which attributes comments to Fousseynou Ouattara, vice-chairman of the Defense Committee, claiming that “terrorists receive satellite data from France and the United States,” is simply unverifiable and was probably never said, but has been repeated word for word by several pro-AES accounts.

Resentment towards France, formerly engaged in Mali, is very palpable in pro-AES accounts; resentment that is exploited for internal communication purposes by the Malian authorities. A fake communiqué attributed to French citizens residing in Mali was widely circulated on X, even though a simple search reveals that the signatory of this letter, a certain Clément Larigne, designated representative of the French in Mali, does not exist.

It should be noted that this resentment did not come out of nowhere: until recently, France played an important role in Mali. In 2022, it was forced to announce the withdrawal of its troops from Mali due to poor relations with the new Malian authorities that came to power following the 2020 coup.

-On November 7, 2025, France called on its citizens to leave the country “as soon as possible.”

-Through official channels (@frenchresponse), it also criticized Russia's change of position in Mali in a short video posted on November 8.

-On November 4, CMACGM, a major French group, announced that it was suspending its land transport activities before changing its mind.

Other powers, regional or global, are concerned by the Malian crisis.

Algeria, which is also at odds with the current Malian government, which has accused Algeria of supporting “international terrorism” at the United Nations General Assembly, is monitoring the situation closely. The country's unofficial position is reflected in posts on accounts suspected of being close to the government. For example, the @algatedz account posted a message announcing that Imam Dicko, who is known to be close to the Algerian government, would be a “consensus” candidate for the transition and questioned his imminent return.

Turkey, which is seeking to expand its footprint in Africa as part of a neo-Ottoman influence strategy (which should be developed in a comprehensive dossier), is also involved. A document leaked on X reveals that a contract was signed “between the head of Malian intelligence, Colonel Modibo Koné, and Turkish manufacturer Baykar, builder of Akinci combat drones. This contract, referenced Baykar 2024-08-1001, was concluded without any involvement from the Ministry of Defense.” If authenticated, this contract would raise questions about Turkey's role in Mali and the divisions within the Malian government.

Les Émirats Arabes Unis ont versé fin cotobre 2025 une "rançon record" de 50 millions de dollars pour la libération de trois otages, dont un membre de la famille royale de Dubaï. Les informations publiques sur ce deal indiquent que celui-ci prévoyait également d'importantes livraisons de matériel, ce qui soulève des questions, sachant le rôle trouble joué par les Émirats au Soudan. Rappellons ici que les Émirats ont également été identifiés par le Wilson Center comme un des pays ayant le plus d'intérêts dans la contrebande d'or malien. At the end of October 2025, the United Arab Emirates paid a “record ransom” of $50 million for the release of three hostages, including a member of the Dubai royal family. Public information about this deal indicates that it also included significant deliveries of equipment, which raises questions given the murky role played by the Emirates in Sudan. It should be noted here that the Emirates has also been identified by the Wilson Center as one of the countries with the greatest interest in the smuggling of Malian gold.

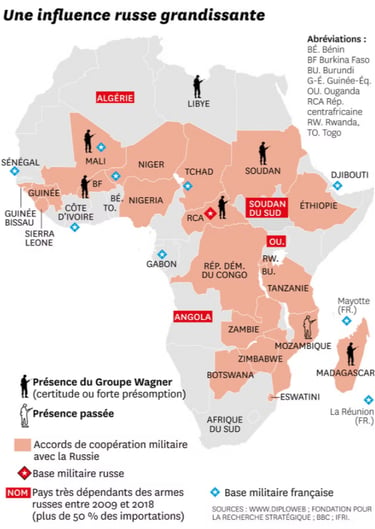

Enfin, la Russie est bien évidemment impliquée au Mali. Son rôle est connu et bien documenté, notamment à travers AfricaCorps (ex-Wagner) et sa coopération militaire avec les autorités de l'AES. La Russie contribue à alimenter le sentiment anti-français, car elle a pour objectif de reprendre le rôle anciennement joué par la France au Sahel. Finally, Russia is obviously involved in Mali. Its role is well known and well documented, particularly through AfricaCorps (formerly Wagner) and its military cooperation with the AES authorities. Russia is helping to fuel anti-French sentiment, as it aims to take over the role formerly played by France in the Sahel.

Uncertainty about the outcome of the clashes is adding to the confusion and the use of propaganda.

The outcome of the fighting remains unpredictable: JNIM is conducting effective guerrilla warfare, with no desire to take major urban centers for the moment, while the FAMa depends on Russian air support, which is less effective against mobile targets. This asymmetry creates a fog of war: it is impossible to confirm the actual losses on both sides, difficult to geolocate events, and communications oscillate between the collapse of the ruling power and the defeat of the jihadists. In this context of uncertainty, each side is amplifying its propaganda: JNIM to boost the morale of its troops, FAMa to legitimize the junta. The lack of a clear resolution (no decisive victory) fuels rumors, forcing an escalation of disinformation on both sides and sowing confusion among the Malian population.

Weak signals and events to watch for

To detect a real shift toward one scenario or another, beyond the noise of social media, any decision-maker or observer will need to carefully monitor a series of weak signals:

Collapse of Bamako's power Probability: 20%

Marked weakening of military power, suggesting an imminent fall of the current regime

Weak signals:

-Increasing number and scale of attacks

-Mass defections of FAMa soldiers (reports of desertions >100/week)

-Repeated failures of fuel convoys escorted by Russian paramilitaries to arrive, causing fuel shortages lasting more than two weeks and civil unrest.

Western, Russian, and Chinese evacuation

FAMa regains control Probability: 20%

Gradual resumption of control of the situation on the ground by the FAMa and tactical victories

Weak signals:

-FAMA air strikes with confirmation of a significant number of combatants, coupled with a decrease in attacks claimed by JNIM;

-Reopening of roads in the south and maintenance of a regular fuel supply to the center of the country.

-Significant increase on social media networks, particularly X, in the number of positive posts from pro-junta accounts (e.g., +50% over 7 days) combined with a decrease in communications from JNIM;

-Effective start of operations at the lithium mine in the Bougouni region and first shipment (around December 2025).

Towards continued insecurity and regional contagion Probability: 60%

JNIM is refraining from taking over major urban areas, as this is costly in terms of human and material resources and exposes them to foreign intervention. JNIM is preparing for a protracted conflict.

Signaux faibles :

-Continued attacks on the outskirts of Bamako and other major urban areas with no widespread offensive;

-Confirmed incursions by JNIM in Burkina Faso and Niger, indicating an expansion of JNIM's activities;

-Repeated attacks in Nigeria (Kwara, as in Oct. 2025) would indicate an expansion of the movement towards the south, which could be hampered by competition with other armed groups

Additonal remark:

A curious trend is emerging: jihadist groups such as JNIM and ISGS are concentrating their activities in Mali's most mineral-rich areas.

October 2025

Classification : Public

credit:brant philip @BrantPhilip_

"MALI CONFRONTED TO terrorism" credit: philip @Seb_MASSON @CArtesdumonde

Positions OF JNIM as of october 22nd, 2025 Credit: @criticalthreats

activities of terrorist groups in Mali and location of the country's main mineral resources

wagner's presence in africa credit:@diploweb